In 1927 Thomas Bulman of Bulman’s Limited spoke to the Vernon Rotary Club about a “dry story” – the development of the dehydration industry in Vernon.[i] The Bulman Cannery dominated the Vernon landscape for fifty years.[ii] Bulman had started the firm in 1916 on a 4,000-acre ranch 16 kilometers north of Kelowna.[iii] The company had begun by dehydrating surplus apples, and when it outgrew the dehydrator in 1926, the operation was moved to Vernon. Two hundred people were employed at the peak of season in 1932, women as well as men. The company prospered during World War II with ever-increasing demands for canned and dried food.

Alice Stevens, a Vernon home economics teacher, joined the war effort as a home economist for Bulmans in 1942.[iv] At the time, almost every imaginable fruit and vegetable that could be grown in the Okanagan was being either canned or dried: asparagus, beans, beets, cabbage, onions, pumpkin, spinach, tomatoes, black currants, greengage and imperial plums in addition to apples of course. The rumour in town was that you could tell what Bulmans was processing every day by the smell in the air. In October of 1942, the Bulman dehydrator began processing only vegetables for four solid months, twenty-four hours a day, for the British Food Mission. In 1943 Bulmans was recognized as Canadian’s greatest producer of dehydrated vegetables of all kinds.[v]

Alice Stevens was responsible for educational publicity and laboratory control at Bulmans, putting her university studies of chemistry and nutrition to use. She borrowed a statement from Claude Wickard, the American Secretary of Agriculture for a speech to the Vernon Rotary Club, telling club members, “Food will win the war and write the peace”.[vi] Conservation of all items that might be used in the war effort was emphasized; an advertisement credited to Stevens appeared in the Vernon News urging “patriotic housewives” to save tin by purchasing larger-sized tin cans. The ad stated that no cans would be allowed for foods low in nutrition and Stevens provided cooking tips: ”Next time you open a can of Bulmans Beans, save some of the beans to add to the supper salad. A white sauce added to the balance makes your creamed beans for dinner go further. There is no shortage of creamed sauce ingredients”.

A bumper crop of summer cabbages in 1944 resulted in the biggest dehydration project that Bulmans had undertaken. The plant employed 215 people to handle 100 tons of cabbage daily. The staff enjoyed a “double-barreled compliment” received from the husband of one of their employees deployed in Italy: “Bulmans cabbage is sure swell; but we wouldn’t mind if the machinery broke down for we see nothing else”[vii].

In 1945 Bulmans started a locker plant for frozen food, open to the general public and popular with hunters, at a time when home freezers were rare. In 1947 Libby, McNeil and Libby Ltd. started negotiating to buy the Vernon plant, and the locker plant was sold.[viii] Over the next three decades, Bulmans tried to keep up with high-yield California products but limited water supply and high freight costs caused the eventual closure of the operations in 1976. In 1980 all of the buildings burned down.

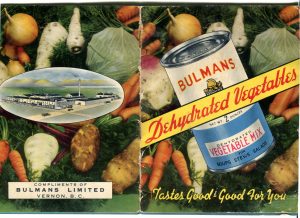

Dried vegetables are uncommon these days, mostly used in soups, but seldom promoted for their nutritional value and excellent keeping qualities. A colourful pamphlet, Bulmans Dehydrated Vegetables, was prepared by Alice Stevens and Phyllis Wardle in 1947. It includes a number of recipes and slogans to promote dehydration of foods. It remains as a sign of how local foods used to sustain Vernon.

Dried vegetables are uncommon these days, mostly used in soups, but seldom promoted for their nutritional value and excellent keeping qualities. A colourful pamphlet, Bulmans Dehydrated Vegetables, was prepared by Alice Stevens and Phyllis Wardle in 1947. It includes a number of recipes and slogans to promote dehydration of foods. It remains as a sign of how local foods used to sustain Vernon.

[i] See Vernon News, February 17, 1927, “Dehydrating provides another market for apples”, Vernon Museum and Archives, Bulman file.

[ii] Viel, H. (1979). Selling agents and fruit and vegetable houses of the North Okanagan 1890 – 1978. Okanagan Historical Society Journal, 43, 11-22.

[iii] See Vernon Museum and Archives, Bulman file.

[iv] De Zwart, M.L. & Peterat, L. (2016). Alice Stevens: Innovations in women’s work. British Columbia History Magazine, 49 (2), 33-37.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] See Vernon News, December 3, 1942, and also A. Bentley, Eating for victory: Food rationing and the politics of domesticity (University of Illinois Press, 1998), p. 142.

[vii] “Summer cabbages”, The Vernon News July 20, 1944, 1, 5.

[viii] According to the Vernon Museum and Archives file, Bulmans refused the Libby offer. The Bulman plant worked closely in product development with the Summerland Research station but the volume was too small and overhead too large for small operations.

I lived in Vernon for several years as a child and I can remember the aroma of tomatoes being canned —in the fall, I believe, in the late 1950s! It is one of my favourite recollections of Vernon along with cycling to Lake Kalamalka. I can’t believe there are no other posts here for Bulmans 🙁

Thanks for sharing your memory!

This was probably a robo response but I would like to think it is from someone who lived in Vernon during the same period….especially since many of my recollections are also from the same period at Christmas time.

Cheers!

No, I’m not a robot. I didn’t live in Vernon at that time, but my colleagues and I aim to restore some of BC’s food history on this site, and Bulmans is an important part of the Vernon food history. The Vernon and District Museum has some files on Bulmans but no one has written very much on it.

Thanks for the note.

I remember in the late 60s , early 70s vacationing here. Seemed my dad always found work for us kids. One summer is was picking peaches, one summer it was Bulmans tomatoes. The guy who hired us said we could eat all we wanted, so of course coming from poverty we ate them right off the vine. Well needless to say after several bouts of upset tummies I didn’t eat tomatoes until a couple of years ago but always love to remember that time. We felt special to think other people were eating tomatoes we picked. lol

Hello Mary Leah – I am in the process of completing a booklet about rail in the Okanagan for Lake Country Museum, and your article has been most helpful. Food processors like Bulman’s (and Sun-Rype) used the railway to bring in supplies and ship out products, big time. The back cover of the Bulman’s recipe book even depicts the plant’s trackside loading platform, which is a great help, because the booklet relies so heavily on imagery. I take it that I should approach the Newman Collection at UFV for permission to republish?

Hello Don

I do not know who owns copyright on the pamphlet. I scanned my own personal copy and I believe the Vernon Museum and Archives also has a copy. The date of the pamphlet is not stated, but Alice Stevens left Vernon in 1947 so it is before then. I suggest you begin with the Vernon Musem as they have the Bulman papers.

Mary Leah

Hi Mary Leah – it won’t be a matter of copyright so much, Bulmans being defunct. Since you have written about Alice Stevens, I would say your collection is probably a more worthwhile source to cite – with your permission, of course.

You have my permission to reference my copy. Thank you for pointing this out on the back of the pamphlet.

Mary Leah de Zwart

Hello Mary Leah. I was excited to find your article about Bulman’s cannery. Thomas Bulman was my great grandfather. My grandfather, Thomas Ralph Bulman, became president of the cannery after the war, and it got away from dehydration and started producing canned vegetables, fruit, tomato sauces and of course ketchup. My father, Peter Bulman, developed most of these recipes (for the sauces), and eventually was president, until it closed in the mid-seventies. I was 16 at that time, so never had the opportunity to carry on in the family business. However, it was a huge part of my childhood, and a great source of pride for our family. Very little has been researched or written about the Bulman’s cannery, so I very much appreciate your article!

Thanks for your email! It was very interesting to research Bulmans to the small extent that I did.

This whole article is so interesting. I didn’t move to Vernon until 1978 (i was 8) so I never knew Bulman’s, but Vernon is home so I’d be curious where this was located. Sad that it burned down just a few years later but once I’d moved here so perhaps I’d remember if I knew where it had been located. Thanks for posting this anyhow!

Perhaps someone can answer your question.

Dear Anne Bulman,

My wife, Patricia, and I are writing an essay on the history of Bulman’s, mainly between 1928 and 1945. We’d be delighted to get in touch with you to learn more about the company’s history, esp. after 1945 (which we wish to deal with in an epilogue). We have worked in the Vernon Archives and have lots of material from the “Vernon News”, and would be delighted to know of any other sources that would add to our understanding of the company’s history.

Our thanks for any help you might be able to offer.

Robert Malcolmson

3-1016 Seventh Street

Nelson, BC, V1L 7C2

tel. (250) 777-1545

I lived about 2 blocks from Bulmans

My mother auntie’s grandmother and my dad worked there some. I also worked night shift on the turn table’s upstairs putting cans on for tomatoes. I think It’ was a good time for the cannery.

A lot of people worked there.

In 1946 I worked between terms at Vernon High as a roust-about at Dolph Brown’s packing House. In the summer, tomatoes were packed into cardboard boxes and shipped out in rail cars. The tomatoes arrived from the farms in boxes on trucks and were unloaded at the upper loading platform east of the packing house. The boxes were then stacked and moved to the graders inside by hand trucks. Somtimes the boxes of ripe tomatoes were spilled when they were moved from the truck onto the ramp. When we “trucked” the boxes of tomatoes into the packing house, we walked over the spilled tomatoes and crushed these. The foreman was Lionel Valaire. He told me to clean up the mess and shovel the slop into steel barrels. I asked him what was done with the barrels of tomatoe slop. He told me that it was taken over to Bulmans to be made into Ketchup. I was only 16 and believed him. Bob Passmore

Great article and so timely since I’m researching on Vernon’s food history. I too would love to know where the cannery plant was located. Sad it burned down in 1980. Perhaps Vera you could let us know since you lived only 2 blocks from there? Thans.

Hi Loretta. I hope you find out the answer to your question. If you are able to get to Vernon I am sure there are many people who could help you.

Thanks so much! I actually live in Vernon. We moved here last year. I think I have found out where the building was located. Loretta

I grew up in Vernon in the 70s and 80s and I had no idea that Bulman’s was a going concern as late as 1976.

I believe Bulman’s was located on the southeast corner of 30th Street and 37th Avenue, just north of what’s currently Forge Valley Storage. In fact, I’m thinking that Forge Valley may be using some of the former Bulman’s space; I don’t believe it all burned down, if I’m interpreting the photos correctly.

Hi Colin. No, Forge Valley Storage was actually an apple packing plant since the early 1900’s. Bullmans was across the street on the lot where 2 large apartment buildings are now located. I was a student at the elementary school one block over when the cannery burned down. It was being used as storage, and several vehicles were destroyed that were stored inside. I remember a 70’s corvette was in there, as I was as real car nut (still am) and we’d nose around the ruins as kids. Hope that helps.

I too would like to know where the plant was located. I think it may have been near the old elementary school (which according to Google Earth is still standing) on the west side of 27th Street. But on the other side of the tracks. But I’m going back more than 50 years so I could be way off. Nonetheless, the articles and comments bring back fond memories!

I was searching the images for Vernon. Low and behold I noticed Bulman’s cannery. I don’t think I was born then but my Mother worked for Bulman’s. I don’t know what year but she mentioned that it was during tomato season. Mom had many interesting stories about the plant etc. She never had anything bad to say about the company. I guess Bulman treated the employees with respect. I am glad that I have found this piece on the archives.

I am enjoying these occasional posts! For me it brings back the aroma of stewing (or whatever process) of tomatoes at Bulman’s. And to this day (about 60 years later), I still sometimes smell them!

https://youtu.be/EDSyb3LsieE

Here’s a guy opening up a 90 year old can of Bulman’s and cooking and eating it!!!!

Your post is interesting. We are going to put your Youtube caution at the start of the video.

“This video was created to see how the product survived over the years and I don’t encourage anyone to try this them self.”

Thanks, and I hope you look at our site regarding Bulmans and its importance in the WW II Canadian effort.

The can is most likely dated between 1939 – 1943 – when Bulmans made an extremely valuable addition to wartime food.

Very fascinating! Even if, as Mary suggests, it’s from the war years, it is pretty old!

My grandfather Metro Ostashek worked the night shift @ Bulmans in the 1940’s & 50’s.

Those were the peak years of Bulman’s production. As you can see in this thread, there have been several articles about Bulman’s in the past few years. I will see if I can post a reference or two.

I moved to Vernon in 1971 and Bulmans was still in operation. I remember well the last product they made, it was pumpkin pie filler. Working for Alpine Distributors, only a block south of Bulmans, we could smell the sweet pumpkin filler as could all of downtown I am sure. After that run the building was rented space for a lot of things. We kept it for storage of Ski-Doos and when the Village Green was under construction all the furniture that was sent up from Mexico was stored there until it was ready to move in. in a way it was the first big storage place in Vernon. I was a bit sad when it burnt down as that also signalled the end of an era that we will not see again.

Thanks for your contribution! So many people have referred to the smells (generally positive) of Bulmans. It is always nice to get another perspective.

Thought you may be interested in this video of a young man opening a 90+ year old can of Bulmans dehydrated vegetable soup and trying it for himself!

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=EDSyb3LsieE

It’s a shame we don’t have a facility like this here in Vernon these days. I remember this from my childhood.

I certainly enjoyed the video and it again brought back memories of growing up in Vernon back in the 1950s. I can still almost smell the aroma of tomotoes presumably stewing in the Bulman’s facility not far from the old elementary school.

Thanks for sharing.